Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) computer scientists have developed a new framework and an accompanying visualization tool that leverages deep reinforcement learning for symbolic regression problems, outperforming baseline methods on benchmark problems.

The paper was recently accepted as an oral presentation at the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2021), one of the top machine learning conferences in the world. The conference takes place virtually May 3-7.

From our partners:

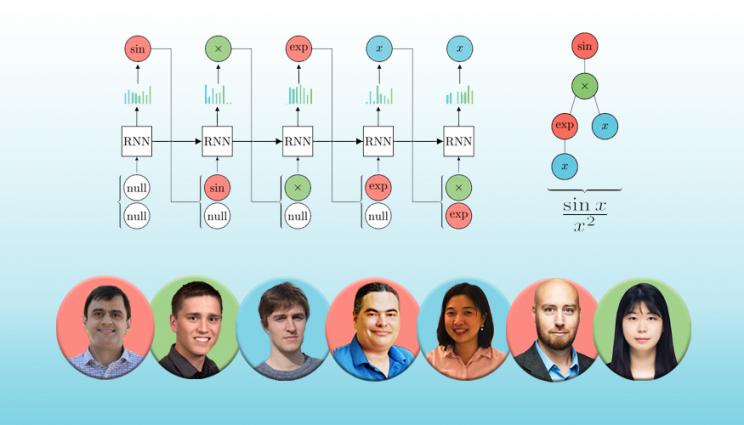

In the paper, the LLNL team describes applying deep reinforcement learning to discrete optimization — problems that deal with discrete “building blocks” that must be combined in a particular order or configuration to optimize a desired property. The team focused on a type of discrete optimization called symbolic regression — finding short mathematical expressions that fit data gathered from an experiment. Symbolic regression aims to uncover the underlying equations or dynamics of a physical process.

“Discrete optimization is really challenging because you don’t have gradients. Picture a child playing with Lego bricks, assembling a contraption for a particular task — you can change one Lego brick and all of a sudden the properties are entirely different,” explained lead author Brenden Petersen. “But what we’ve shown is that deep reinforcement learning is a really powerful way to efficiently search that space of discrete objects.”

While deep learning has been successful in solving many complex tasks, its results are largely uninterpretable to humans, Petersen continued. “Here, we’re using large models (i.e. neural networks) to search the space of small models (i.e. short mathematical expressions), so you’re getting the best of both worlds. You’re leveraging the power of deep learning, but getting what you really want, which is a very succinct physics equation.”

Symbolic regression is typically approached in machine learning and artificial intelligence with evolutionary algorithms, Petersen said. The problem with evolutionary approaches is that the algorithms aren’t principled and don’t scale very well, he explained. LLNL’s deep learning approach is different because it’s theory-backed and based on gradient information, making it much more understandable and useful for scientists, co-authors said.

“These evolutionary approaches are based on random mutations, so basically at the end of the day, randomness plays a big role in finding the correct answer,” said LLNL co-author Mikel Landajuela. “At the core of our approach is a neural network that is learning the landscape of discrete objects; it holds a memory of the process and builds an understanding of how these objects are distributed in this massive space to determine a good direction to follow. That’s what makes our algorithm work better — the combination of memory and direction are missing from traditional approaches.”

The number of possible expressions in the landscape is prohibitively large, so co-author Claudio Santiago helped create different types of user-specified constraints for the algorithm that exclude expressions known to not be solutions, leading to quicker and more efficient searches.

“The DSR framework allows a wide range of constraints to be considered, thereby considerably reducing the size of the search space,” Santiago said. “This is unlike evolutionary approaches, which cannot easily consider constraints efficiently. One cannot guarantee in general that constraints will be satisfied after applying evolutionary operators, hindering them as significantly inefficient for large domains.”

For the paper, the team tested the algorithm on a set of symbolic regression problems, showing it outperformed several common benchmarks, including commercial software gold standards.

The team has been testing it on real-world physics problems such as thin-film compression, where it is showing promising results. Authors said the algorithm is widely applicable, not just to symbolic regression, but to any kind of discrete optimization problem. They have recently started to apply it to the creation of unique amino acid sequences for improved binding to pathogens for vaccine design.

Petersen said the most thrilling aspect of the work is its potential not to replace physicists, but to interact with them. To this end, the team has created an interactive visualization app

for the algorithm that physicists can use to help them solve real-world problems.

“It’s super exciting because we’ve really just cracked open this new framework,” Petersen said. “What really sets it apart from other methods is that it affords the ability to directly incorporate domain knowledge or prior beliefs in a very principled way. Thinking a few years down the line, we picture a physics grad student using this as a tool. As they get more information or experimental results, they can interact with the algorithm, giving it new knowledge to help it hone in on the correct answers.”

The work stems from a Laboratory Directed Research and Development program-funded initiative on Disruptive Research, a portfolio composed of projects considered to be high risk and high reward.

Co-authors included Nathan Mundhenk, Soo Kim and Joanne Kim. LLNL machine learning researcher Ruben Glatt has since joined the team. The work also was furthered by several students from the University of California, Merced whom Petersen mentored during LLNL’s 2019 Data Science Challenge Workshop where it was featured as a challenge problem. LLNL has released an open-source version of the code, available here.

For enquiries, product placements, sponsorships, and collaborations, connect with us at [email protected]. We'd love to hear from you!

Our humans need coffee too! Your support is highly appreciated, thank you!